Shawn Syms writes stories that push boundaries–of identity, compassion, of what it means to be alive and human at this particular moment in time. I’m a big fan of his work, in particular the deep respect and humility he offers his characters, allowing space for the many complex edges of their lives to co-exist and intermingle fully, without judgement.

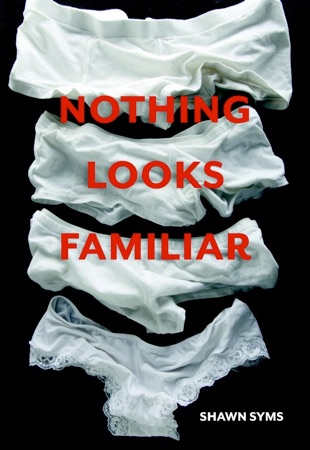

The publication of his first collection Nothing Looks Familiar is cause for celebration. Within these twelve stories we come face to face with loneliness, desire, heartbreak, tragedy, and–most importantly–resilience. In a Shawn Syms story, no one is simply a victim. While his characters confront often painful, even devastating circumstances–poverty, addiction, disease–they are, as we all are, fully and tenderly human, reflecting back our own stubborn hopes and paralyzing fears. Nothing Looks Familiar was mentioned among the National Post’s top books of 2014. Shawn Syms edited Friend. Follow. Text. #storiesFromLivingOnline, an IndieFab Book of the Year Silver Award winner. He’s currently at work on his first novel.

TC: Congrats on the publication of Nothing Looks Familiar, Shawn. It’s such a great collection. Can you tell me more about the process of putting it together? Were the stories in the collection written over a long interval?

SS: I wrote the stories in Nothing Looks Familiar over the span of a decade. I’m going to try and finish the next one a bit more quickly!

Though I’ve done various forms of journalism for a range of publications since the late 1980s, I turned to fiction after a major life event more than ten years ago, looking for a subtle and nuanced way to try and explore some of the same things that have preoccupied me in my journalism and about the world more generally: issues that generally have to do with sex, drugs, and queers—and by that I mean outsiders and non-conformists of every stripe, not just in terms of sexual identity.

I wrote the book while studying literary craft with a bunch of great teachers including Marnie Woodrow, Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer, Paul Quarrington and Douglas A. Martin. While pulling these strange stories out of myself, I was spending a lot of time learning what works and doesn’t work in short fiction and novels, which I’ve parlayed into a bit of a minor career as a literary critic for a bunch of publications including Quill and Quire, The Rumpus and Lambda Literary. So I was toggling back and forth between critical writing and the book. And my day job. And life in general.

TC: One of the things that impressed me most in the collection is the great range of voices and narratives. You’re equally comfortably inhabiting the mind and body of a struggling female fraud artist (“Family Circus”) as a young, ostracized boy (“The Exchange”) Do you have a favourite character or narrator in the collection? Were any a particular challenge to write?

SS: Thanks for the compliment—and the great question, Trevor. One of the most interesting characters for me is Adam in “Four Pills,” a young jobless guy who spends a lot of time in a downtown Toronto park that’s known for both drug use and queer sex, in both of which he dabbles. Adam represents a certain ambiguous tension between behaviour and identity—he has done things that others would say call for categorical labels, but he doesn’t define himself on their basis.

If one man’s mouth has enveloped another man’s penis, does that make either of them “gay”? There are people—both gay and antigay—who would insist the answer is yes. But a more interesting and realistic response is that, as they say on Facebook, “it’s complicated.” And that messy question of sexual identity really only scratches the surface of what this story—which also involves sex work, crack, thievery and sexual assault—is about.

TC: You also write wonderfully and truthfully about sex. One of my favourite scenes was the long fantasy/masturbation sequence in “Taking Creative License,” which is simultaneously funny, true-to-life, and deeply tender. In a recent interview with Angie Abdou, we talked about how sex is often absent from Canadian literature. Why do you think that is? And do you enjoy writing about sex?

SS: I recently read that female-masturbation scene to a crowd, and I’m happy to say it was a huge hit! I think writing about sex is both difficult and necessary. Difficult both in the sense that it can be hard to imagine in our sex-negative culture, and in the sense it requires a delicate touch and is easy to screw up. When I write about sex, I try to be direct—I think this is not only better in terms of craft, I think it’s valuable from a political perspective. (While I’m on the topic of bold sexual writing, I need to give a shout-out to Greg Kearney’s novel The Desperates, which talks about rough [consensual] sex in ways that are at once blunt and elegant.)

Sexual writing that is daring and uncircumscribed is a necessary part of Canadian literature, because our society is screwed up when it comes to the politics of sex and the body, in ways that are so profound they can sometimes seem invisible. But if you live in a province where you can’t get an abortion, you see it. If you’re a person with HIV who can be thrown in jail for completely harmless sex acts, you see it. If your lot in life has been significantly shaped by your body and the structures that regulate you because of it—say, if you are a woman, especially if you are a transsexual woman or a sex worker—you see it.

Our bodies are commoditized through mass media at the same time as our desires are stigmatized and controlled through apparatuses of power. Writing and reading and talking without shame about our sexual desires and practices is not just a valuable deprogramming exercise, but ideally part of a broader process of dismantling the systems that maintain these social inequities. And it’s fun and hot.

TC: One of my favourite stories (although it’s hard to pick just a few) is “The Eden Climber,” about two sisters, Cassandra and Ruthann, who live together in a nursing home. Among other things, the story explores sexual desire in the elderly—a subject that’s almost taboo, it’s so invisible in mainstream culture. Can you talk a bit more about this piece? Why was it important for you to write?

SS: People remain sexual beings as they get older and as they lose various faculties, though especially in an institutional setting this reality can be fraught with challenges and complexity—and the risk of abuse. In fact, while working on this story I did a lot of research on the issue of elder sexual abuse. I learned things that I found quite frankly incredibly shocking—for instance, the significant proportion of sexual abuse of elderly women that is perpetrated by their own sons. In this story I wanted to explore a situation that arguably involves an abusive power dynamic but also an aging woman articulating and acting upon her own desires.

“The Eden Climber” was also an exercise in telling a story from the point of view of an unreliable narrator. Cassandra is not particularly likeable and her biases—regarding her own sister’s intelligence, about the nursing-home staff’s level of competency—are glaring. In telling this story from Cassandra’s perspective, I was directly influenced by the compelling novel Property by Valerie Martin.

Property is told from the point of view of Manon, the wife of a slave owner in the U.S. South who sees herself in competition with a slave named Sarah for the affections of her husband. Like Cassandra in “The Eden Climber,” Manon is trapped in a position of both oppression and privilege, and possesses a startling lack of self-awareness. Property ends with Manon making a statement that is at once completely in keeping with her character, yet profoundly absurd when seen in broader context—and I attempt something similar in my story as well.

TC: You also show consistently deep compassion and respect for your characters, many of whom live on the margins of society. I’m thinking of Wanda, the narrator of “On the Line,” who juggles an intensely physical job as a meat-cutter with severe loneliness and a sense of displacement that so many of your characters share. Why are you drawn to characters like Wanda, who are down on their luck but still—mostly—hopeful for a better future?

SS: Well, this is life. Today, at any rate. The elements of global capitalism effect profound alienation on so many different people in so many different ways. But still, every day we find ways to resist forces that would disconnect our minds and bodies, and instead carve out lives of pleasure and meaning—we find one another, we love one another, we engage in creativity and play for greater social good or simply for its own joyful sake. So often, despite everything thrown at it, the will to live is strong.

TC: You’re a noted critic and reviewer and a keen eye on the Canadian literature scene. To put you on the spot, what’s your current take on the state of our nation’s literature? Any trends you’re noticing in the industry of the work that’s being written at this moment in time?

SS: The vast majority of what I read day-to-day is current Canadian literature—this is in part because there is so much to read and so little time to do it that I mostly only read books that I’m being paid to write about! I can’t really offer any profound sweeping analysis of Canlit as a whole, other than to say that in addition to the boring and predictable stuff that many people complain about, there is a lot of exciting writing emerging from Canada right now.

I’m excited about sites like Little Fiction that are helping democratize access to short stories, and helping launch careers for a new generation of talent. (Editor’s note: this feels like a good time to point out that this interview was originally posted on Trevor’s site. Also, thank you, Shawn.) I’m excited by the evolving careers of established writers like Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Miriam Toews, who put out books last year that were both profound and completely eviscerating. I’m excited about fresh new voices such as Doretta Lau, Gail Megan Coles and Chelsea Rooney. I’m excited about novels like Moving Forward Sideways Like A Crab by Shani Mootoo, which is not only formally innovative but places a transsexual character centrally. So from where I sit, there’s lots to be excited about when it comes to Canlit at the moment.

TC: Finally, what’s next for you, Shawn? What are you working on currently?

SS: I’ve tinkered with a few different ideas in the past year or so. I’ve recently started work on something new that I think I will see through. It’s a novel—a decision that I have to admit is heavily influenced by (my perception of) market forces, though the form will also present an interesting new creative challenge for me. It’s on themes of social and economic class, which are a huge personal obsession for me having grown up staunchly working class. But, without giving too much away, I think it explores these topics in a way that’s unlike any Canlit I’ve ever read before. Some of the core elements to the story are things that I suspect many people will find quite bizarre and unusual—which means I can’t resist going there.

LINKS

Purchase NOTHING LOOKS FAMILIAR from:

Arsenal Pulp Press | Powell’s | Indigo | IndieBound

Read two stories from the collection here at LITTLE FICTION:

This interview was originally published at Currently Living, the online home of Trevor Corkum.

HOME | INTERVIEWS | STORIES