LF: Let’s start with the big stuff, congratulations on the novel. How has it been being a fully-fledged published author?

AL: It’s been great! So strange, in some ways, but so wonderful too. I think as a writer you get used to—especially with a debut novel—feeling like your novel is never actually going to make it onto bookshelves. It’s such a long process, getting from that manuscript to the finished product. When you first get that offer on your book it’s tremendously exciting, and then you settle down into the editing and the revising and the waiting and after a while it starts to feel as though the book is never going to arrive. It’s always going to be in the shadowed, “preparing for publication” stage. But then all of a sudden those years of waiting are up and your book is out there, in the world. It’s a strange and wonderful feeling and worth every single angsty dream I had about it in my teens.

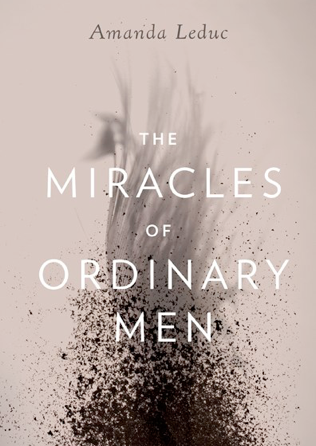

LF: The Miracles of Ordinary Men started (in part) with a short story. How did the decision come about to build a novel around it?

AL: At the time, it didn’t feel so much like one decision as it did a culmination of a series of smaller decisions. I’d written a short story about an angel when I was sixteen, and I kept returning to and re-writing that story over the course of the next ten years. I wrote it from different viewpoints and introduced, then took away, different characters. The main basis of the story stayed the same, though—I had this character, this angel, who was bald and skinny and blue-veined and trembling. An odd creature who didn’t seem very angelic at all. One of the versions of this story went over well in my senior workshop at UVic, and for a while I just thought it was meant to stay as a short story, and tried to send it out. Then, when I was doing my Masters degree in Scotland, I wrote another story about the angel but tried to look at it from the point of view of a human man who became that angel – how he would feel about his transformation, how that would all play out. At the beginning of 2008 I decided to scrap my original thesis plan—I’d written another novel the year before, in 2007, and had gone to graduate school thinking that I would write part of the sequel to this original novel as my thesis. But in January I abandoned that idea and started to pull these stories together, and by May, when my thesis was ready to submit, I had the novel plotted out in my mind and ready to go.

The actual writing of it, of course, took a great deal longer than I expected. These things always do.

LF: What can you tell us about the novel?

AL: It’s a novel about transformation, I suppose—both physical and spiritual. It follows two main characters in alternating chapters: a man named Sam, who is still grieving the fiancée who left him two years before, and who wakes up one day to find himself growing wings; and a woman named Lilah, who is consumed with worry and guilt over her brother, Timothy, who is homeless in Vancouver. Both Sam and Lilah are lost souls searching for answers—the kind of people who are skeptical of and yet secretly hoping for miracles in their own lives. As a writer, I wanted to see how they would react when faced with miracles that were unlike anything they might have dreamt of.

LF: What inspired the novel?

AL: I’ve always been fascinated by angels, and miracles in general, but what interests me the most about them is how inevitably, those who experience miraculous occurrences always end up feeling somewhat isolated from the rest of the people that they know. For some reason it always seems like experiencing God in a direct way—whether or not God actually exists is sometimes, I think, beside the point, as the experiences of these people are always real enough to convince them otherwise—leads to an inability to communicate the feeling. And I’ve always found that sad, because as a culture—especially in a society with a Judeo-Christian basis such as ours—we tend to view miracles as these amazing, wonderful things. But when I was writing MIRACLES I couldn’t shake the idea of a miracle as being something potentially quite terrifying. How, I wondered, would a man or woman feel if they were at the centre of that terror, surrounded by people who persisted in thinking that the miracle was in fact something wonderful? How would you feel if even those you loved could not understand you, or see what was happening? How would it feel to know that God was working magic in your body and heart but remaining silent to all of your angry, shouted prayers? These are all things that I thought about while I was writing the book. And they’re all, obviously, questions that I don’t think I’ll ever have the answer to. I don’t think anyone ever really does. But as a novelist, it’s fun to be able to shape an approach to these questions, to get yourself thinking and wondering and hoping that what you’re putting down on the page might make sense to another reader, and perhaps get them thinking and hoping too.

LF: In your interview with Jessica Kluthe, you mentioned that The Miracles of Ordinary Men was rejected by twenty-nine publishers. How was that experience? And how was it when the novel found a home with ECW?

AL: Well—it was hard. I’ll say that much. I’d spend the majority of 2010 revising the novel with my agent, and we sent the novel away to the first round of publishers on the very day that I returned to Canada. I’d been living in Scotland for the previous three years, and I’d had every intention of staying there forever. But I wasn’t making enough money, and in November of that year my visa ran out and I couldn’t afford to extend it, so home to Canada I went. And because I had no money, I moved back in with my parents for a while. So the novel went out, which was exciting, and it was exciting to be home, too, because I’d missed everyone so much. But a week after my agent sent the novel out, I started getting rejections for it, and right about this time I started missing Edinburgh and my life there and wondering how the heck I was ever going to get my feet back beneath me again, living in my parents’ house as I was, unemployed, way out in the middle of the country. I didn’t even have my driver’s license, because it had expired while I’d been living in the UK.

So, yes. Every publisher rejected it during that first round of submissions. My agent and I talked about the book over Christmas and I revised again in January—the only blessing about not working was that I had all the time in the world to revise—and then we sent it out to the second round of publishers, who all rejected it too. I was still unemployed, still without a driver’s license, still pretty much convinced I was a failure. Fast forward to April, when we sent it out to a third and final round of publishers. At this point, I’d started working part-time at a hospital in Hamilton. It definitely hadn’t been my first choice for a job, but it paid well and my mother worked at the same hospital so we could ride into work together, which was great—because there was still no driver’s license!

Things started to change, but so slowly I almost couldn’t recognize it. I started to pay down some debts. I eventually had enough money to get my driver’s license again (yay freedom!), and by the time the summer rolled around I had even managed to save for a little vacation. I went back to Edinburgh that summer, for the wedding of two friends. I was so thrilled to be back, and instantly felt at home and okay as soon as my plane touched down. The wedding was wonderful, and right at the beginning of my stay, so I had almost two weeks of Scotland time to enjoy. The day after the wedding, a bunch of us got together at my friends’ apartment and feasted on leftover wedding food and cake. I was so happy then, and I remember holding a glass of red wine in my hand and sitting on their couch and thinking, “It’s okay. You’ll be okay, even if the book doesn’t find a home. Book or no book, you can make a life for yourself. Book or no book, you are happy.”

And—no word of a lie—half an hour later I checked my email and the offer from ECW was sitting in my inbox.

It’s such a funny story, and such a great one. The kind of thing that you hear and think, “Yeah, right—that totally didn’t happen! She’s making that up!” But it did happen exactly like that. And now I have a great path-to-publication story to tell, which almost makes that eight months of suffering worthwhile.

If I hadn’t had my agent cheering me on through the whole process, though, I’m convinced I would have given up. For sure.

LF: Your writing is often described with terms like “fantastic realism,” “lyrical” and “unsettling” — has your writing always been like that or was this a voice that eventually found you?

AL: It’s probably a bit of both, I think. There was that angel story I wrote when I was sixteen—I remember feeling very nervous about that story, and unsure if it would go over well because it was quite dark and strange. Even though it eventually was well received—by my high school English teacher, who read it for an assignment in class, and then again in that senior workshop at UVic—I tried not to write things like that for a while. When I was completing my undergraduate degree in writing, I tried hard to write stories that were “literary”, whatever the heck that means, even though in many cases I was still writing stories about God and questions and things like that. I had this idea that stories about strange angels and miracles and magic were not the kind of thing that would generally get one good marks in workshop, or get one recognized/get one published. It was a ridiculous idea, and I realize that now, but at the time I was convinced that that was how things went. (It’s especially ridiculous when I look back and remember that that senior workshop class did indeed look at a revised version of the angel story, and loved it. But I was convinced, and there was no telling me otherwise.)

So for a long time I denied that voice. It wasn’t until I’d moved to Scotland and gotten about halfway through my Master’s degree that I really embraced the magic that wanted to come out in my writing.

LF: The thing that I personally love about your work is that for as fantastical as it can get, it’s always rooted in a human truth or emotion. What draws you to the fantasy aspect?

AL: One thing that I love about fantasy, and I suppose about magic realism in particular, is the ability that these magical occurrences have to shine a light on all aspects of a character. When you take an ordinary person and drop them into extraordinary circumstances, it’s as though the person that they are becomes magnified a thousandfold. Fantastical occurrences, for me, are a way of really forcing a person to confront the realities of their own regular life. In the case of Trevor, the protagonist in my Little Fiction story, Asking For Change, I wanted to use the occasion of a miracle—i.e. the visit from the altogether un-magical Val, the Tooth Fairy—as a way of highlighting Trevor’s own regular feelings, the ones that he hasn’t owned up to. His dissatisfaction with the way that his life has turned out, his fear and guilt over the ambivalence that he feels toward his son. In the case of MIRACLES, the occasion of a miracle is forcing Sam to confront his own inability to move beyond his grief. To take action in his life instead of passively allowing life to happen to him.

LF: You wrote that you worked on The Miracle of Ordinary Men for five years. Writing a novel is obviously a different experience to writing short stories—is there one you prefer?

AL: I’m not sure! As a knee-jerk reaction I want to say that I prefer writing novels, as I like the space and time that novels give you to breathe, to reconsider, to be messy. But the best short stories do that too, so I guess it’s a silly thing to say. They’re both intensely different writing experiences. I think I tend to be somewhat more ruthless more easily when it comes to short fiction (this might be hilarious to anyone who has workshopped a story with me in recent months, in which case I apologize)—I tend to pare my language down more quickly than I do when writing a novel, and I’m more sensitive, in a short story, to how much I can say in a shorter space.

Which is not to say that I’m not sensitive to these same kinds of things when writing a novel. But a novel is a larger canvas, and there’s more room, I feel, to muck around and take chances and leave things open-ended. I love how short stories hint at things—how the spaces in a short story can often encapsulate and encompass so much. But sometimes it’s fun to dive into those spaces, and explore them, and in a novel I feel like I can do that.

Also, for what it’s worth, every novel I’ve worked on thus far has come out of a short story. So I think there’s something in my writer brain that always wants to go beyond the shorter space.

LF: Your Little Fiction story, Asking For Change, has a small link to the novel — was that coincidental, or is it a theme you wanted to carry on into its own story?

AL: Most of my ideas tend to come from very small things. In the case of MIRACLES, the novel eventually came about because I had this tiny little idea about this un-angelic angel that wouldn’t go away. And Asking For Change came about much like that—I wrote MIRACLES, and there was this little line in the novel (Tomorrow, the Tooth Fairy would show up at his door, dressed in rags and asking for change) that took root in my head and wouldn’t leave. After a while it was as though the sentence had its own little pulse, and a year or so into the revisions of the novel I realized that there was another story wanting to come out in that sentence. So I drafted a short story, and then promptly forgot about it as the revisions for MIRACLES got more intense. I didn’t revisit the story until the latter part of 2012, at which point I took it up again, erased most of it, and wrote the thing more or less from scratch. Most of my short stories happen that way.

One of my instructors at UVic, Carla Funk, once told us that as a writer you should always explore the possibility of cannibalizing your own work. You should be able to go back to stories and poems and novels that you’ve previously written, and go through them, looking for other things that might feed your next story. This has worked in plenty of cases for me—many thanks to Carla for such great advice!

LF: Speaking of Asking For Change, and without giving too much away, much of the story involves a character’s teeth falling out. Are you one of those people who has dreams of her teeth falling out?

AL: Ugh, yes. I had braces when I was younger and every few weeks or so I’ll dream about my teeth. Sometimes they fall out. Sometimes I wake up (in my dream) and discover that my teeth have reverted back to how they looked before I had braces.

On the plus side: it’s good motivation to keep me brushing and flossing.

LF: You have work coming soon to filling Station, The Maynard and Existere—what can you tell us about any of those, and do you have anything else forthcoming?

AL: filling Station and The Maynard are both publishing tiny little flash fiction pieces of mine—the filling Station piece is out now, in issue 56, and the piece in The Maynard should be coming out in the next month or so, I believe. I really enjoy exploring the flash fiction form. In flash fiction, every single word matters in a very visible way—it’s the closest I’ll ever get to writing poetry. (And that’s a good thing, because I’m a terrible poet.)

The Existere piece is a personal essay. I didn’t study creative non-fiction during the course of my undergraduate degree, and only came to it in my mid-twenties, when I was doing my Master’s. And I fell head over heels in love with the form then, when it happened. It’s been deliciously lovely to see some of my personal essays finding homes in the publishing world. Next to novels, I’d have to say it’s my favourite form in which to write.

LF: What are you currently reading at the moment?

AL: I’ve just finished Studio Saint Ex, by Ania Szado, and I’m currently re-reading The Dustbin of History, by Greil Marcus, as well as Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Once those two are done (or heck, maybe even before) I’ll be digging into Saleema Nawaz’s Bone and Bread, which I’m really looking forward to.

LF: Do you have writing rituals? Location, music, etc.?

AL: I usually write to music, though in recent months I’ve discovered that white noise boosts my concentration. (See here: www.simplynoise.com) When it’s music, it’s either cello (Zoe Keating is a huge fave), other instrumental records, or Florence + the Machine. I wrote most of the final draft of MIRACLES with Ceremonials on perpetual repeat.

There’s always tea around when I write. And—might as well just come out and say it—I do most of my work in my pyjamas. I have a great rooftop deck that I write on during the summer—when I have a writing day I’ll usually write outside for a few hours in the morning, before it gets too hot, and then slink back inside and write at my desk for a little bit more. If I can get 1,500 words in a day I can stave off the guilt until the next morning.

That’s a “best case scenario” kind of day, though. Most days I write one or two hundred words, if even that, and spend the rest of the time checking Twitter, or my email, or making muffins. Also, episodes of House of Cards, Grey’s Anatomy, playing piano, playing violin scales, cleaning the bathroom/kitchen/bedroom, dusting, etc etc.

LF: May has been proclaimed as short story month—can you tell us what is that you like about reading and / or writing short stories?

AL: What I love most about short stories, as I talked about above, is their ability to hint at things. I love how short stories invite the speculation on the page into the telling, and how they can be so precise and yet so open all at the same time. And it’s for exactly this reason that I find them so difficult to do, myself. Maybe that’s why I prefer novels, at the end of the day? Maybe not? (Because of course writing novels isn’t “easier”, it’s just… different.)

I think I’ve reached the point in the interview where I stop making sense.

LF: What are some of your favourite short stories?

AL: My favourite short story that I’ve read in recent years is “The Dead Are More Visible”, from Steven Heighton’s collection of the same name. It’s a straightforward narrative that basically details one scene—a confrontation between a woman icing a rink late at night and the youths who try to cause trouble for her. But there’s layer upon layer of backstory packed into almost every sentence, so that it becomes much more than just a re-telling of that scene. It’s beautiful and dark and sad.

Same goes for “Safari”, from Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad. Another great example of a story that leaps outside of the time of its telling—I love how Egan so deftly captures the lives of her characters in just one or two sentences. So great, and definitely worth a read if you haven’t yet picked it up.

LF: How is Bare It For Books going?

AL: Very well, thank you for asking! We have almost all of our photos now and are getting the calendar design in place, slowly but surely. We’re really looking forward to seeing what that final product is going to look like, not least of all so we can show everyone who’s donated so much time and enthusiasm to the campaign thus far.

LF: Other than Bare It For Books, what are you currently working on?

AL: I’m at work on a new novel, which I hope to have “finished” (and by that I mean a workable draft that I can show to my agent without the need for a subsequent year of revising, as was the case with MIRACLES) by the end of the summer. I’m also hard at work on a number of personal essays which I’d like to start submitting to journals in the next few months as well. But we shall see about all of that, I suppose. In writing, as in life, I find my best intentions often go astray.

LF: Seeing as how the calendar features published Canadian authors, any chance you’ll end up in the 2015 calendar?

AL: Ha! Thanks for asking, Little Fiction folk! I can confidently say, however, that the answer is most likely no. We’ve had such a great response to the Bare It For Books project, and there have been plenty of literary lady volunteers who’ve offered to be in the 2015 calendar. So there will be no need for me to fill a spot. Which is good, because the last thing I’d want anyone to think is that Bare It For Books is some kind of vanity project. Because it is most definitely not. ;)